Still, I couldn’t help but compare my own work schedule-defined as it was by a demanding editor, deadlines, and ever-shrinking budgets-with Tintin’s. It's hard to say whether Tintin played a direct role in my choice of career, but the books certainly influenced me enough to want to read and write for a living. Years later, before the medium fell on hard times, I found myself working at a newspaper. In short: He comforts the afflicted, and embodies the values of honor and loyalty to friends. Tintin, after all, works against Imperial Japan and European dictatorships, befriends Chang, fights slavers, and defends the Roma. Rereading Tintin also provides a much more complicated image of Hergé. Tintin works against Imperial Japan and European dictatorships, fights slavers, and defends the Roma. There were things that I loved about Tintin that made it easier to reject those things I did not-without ignoring them altogether. What those comics taught me was that heroes, even boyish, never-aging ones like Tintin, are deeply flawed, and if you ruminate on something long enough, even a cherished childhood memory, you will inevitably see those flaws clearly. But I couldn’t entirely disavow the series. There’s certainly irony in a child of the former colonies idolizing a character who might be dismissed by casual critics as a proxy for the white-man’s burden (and by more serious ones as a racist). In another, he resolves a dispute over a straw hat, leading a member of the tribe to say: “White master very fair. In one frame in Congo, an African tribe worships Tintin. Neither comic was available in English until decades later, and it was then that I read them with a mixture of horror, amusement, and embarrassment. In 1930’s Tintin in the Congo, the Belgian hero’s adventure takes him to his country’s former colony where he “civilizes” the natives (who are portrayed with a combination of paternalistic racism and inferiority), and slaughters animals as a big-game hunter. The first two comics are the most controversial: Tintin in the Land of the Soviets, first serialized in 1929, is so transparent in its anti-communist propaganda that Hergé himself tried to suppress its publication in later years. His work on a wartime newspaper allied with the Nazis is well documented, as is the fact that some of his earliest Tintin books disseminated far-right ideas to children.

As I grew older, I learned more about Hergé, Tintin’s creator whose name adorned the top of every album (the name is a play on the inverted initials of his name, Georges Remi). With age, I could add one more thing: familiarity.

#THE ADVENTURES OF TINTIN SERIES SERIES#

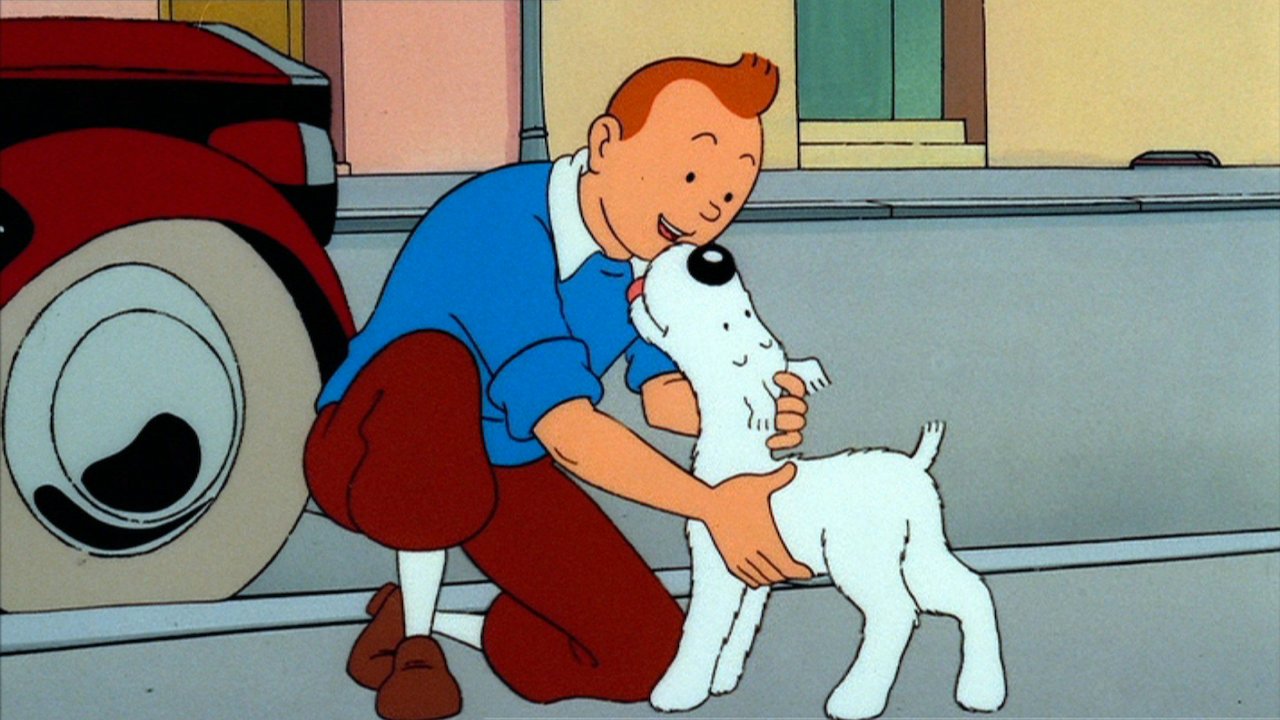

But what continues to appeal to me most about Tintin is what attracted me to the series in the first place, the common thread that runs through all the albums: friendship, loyalty, adventure, and, to use a word seldom used anymore, honor. The serialized books- Red Rackham's Treasure and Secret of the Unicorn, Seven Crystal Balls and Prisoners of the Sun, and Destination Moon and Explorers on the Moon-are still appealing, more now for how different they are than for their narratives. Flight 714, a story I loved when I was younger, possibly because of the UFOs, hasn’t aged well for exactly that reason Castafiore Emerald, dull when I was a boy, is now among my favorites, precisely because it’s about nothing.

Over the years, my favorites changed, as did the things I saw in them.

The yeti’s longing for permanent friendship mirrored my own Tintin’s friendship with Chang was the kind I wanted. My favorite in those days was Tintin in Tibet, a comic whose final frame still makes me emotional. And I counted the days until we visited an uncle who owned the entire collection and guarded it jealously in a locked cupboard, to be retrieved when I visited upon the condition it was treated carefully-a condition I’m happy to say I satisfied. Wheeler bookshop at Churchgate station for the princely sum of 18 rupees. I read and reread the albums we had I beamed when my father, whose love for Tintin I inherited, bought a new album home from the A.H. We moved every year from one far-flung part of Bombay, as the city by the sea was known then, to another: moves forced by parental job changes and familial instability that meant new homes, new neighbors, new schools, and new friends. Few things in my life were permanent at that time.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)